UNICEF Warns Pandemic Could Cause Spike in Stillbirths

With the release of new global data, UNICEF and partners call for collective action against a "neglected tragedy."

In late September last year, Christine Wangechi of Kenya lost her second child. The baby was stillborn.

"It was a shattering moment," Wangechi recalled. The problem was that she had preeclampsia, a pregnancy and childbirth complication that can put the life of both the mother and baby at risk. By the time Wangechi's condition was detected, it was too late. Her son died in utero at 30 weeks.

Now Wangechi is sharing her story publicly to help spread awareness of stillbirth and to encourage women to seek quality antenatal care as a way to prevent it. "It's alarming how many babies are lost every year," she said during a virtual global discussion about the issue, co-hosted by UNICEF over Zoom on Oct. 21. "When my baby died, I thought I was the only one."

Nearly 2 million babies were stillborn in 2019. That amounts to one stillbirth every 16 seconds, according to a new report released by UNICEF, the World Health Organization and the World Bank Group.

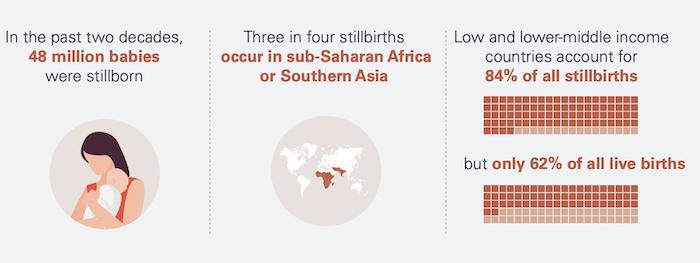

A few of the top-line findings of A Neglected Tragedy: The global burden of stillbirths, a report released by UNICEF, WHO and the World Bank Group. The report contains estimates by the United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME) on the number of babies that are stillborn every year due to pregnancy and birth-related complications, the absence of health workers and basic services. The report further warns that the COVID-19 pandemic could reverse decades-long progress on the issue.

While that figure represents progress since 2000, stillbirths haven't declined as rapidly as maternal and newborn mortality has over the same period. If current trends continue, there could be another 19 million stillbirths before 2030.

And then there's the COVID-19 factor. In the next 12 months, stillbirths could jump by as many as 200,000 globally — more fallout from the sudden and intense effects of the pandemic on already struggling health systems.

A stillbirth is a baby born with no signs of life after 28 weeks of completed gestation. (Neonatal deaths are counted separately.) Most stillbirths are preventable, often the result of poor quality care during pregnancy and at time of delivery. Two-thirds of all stillbirths could be avoided with low-cost interventions, such as routine screenings during pregnancy for hypertension (high blood pressure), a sign of preeclampsia, and high blood sugar, a sign of gestational diabetes, both treatable conditions.

An overwhelming majority of stillbirths — 84 percent — occur in low and lower-middle income countries where ensuring access to quality maternal and newborn health care services has long been a challenge, and where COVID-19 response measures have deeply disrupted essential services.

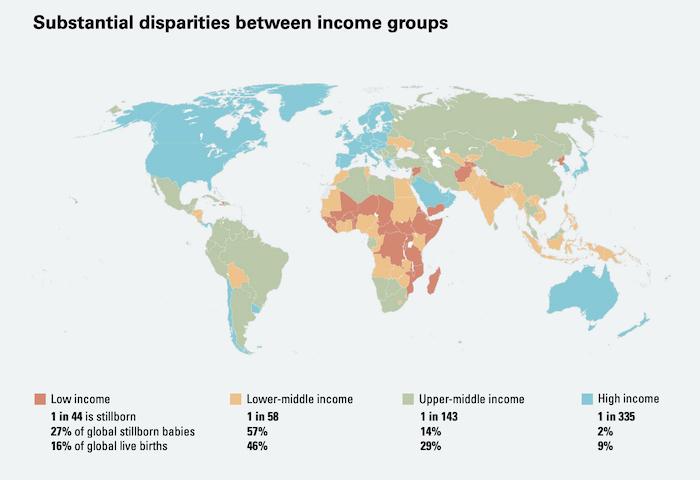

This map illustrates the wide disparities in stillbirth rates between countries. One in 44 babies are stillborn in low-income countries, accounting for 27 percent of the total worldwide. In high-income countries, one in 335 babies are stillborn, accounting for just 2 percent of the global total. There are also sharp disparities in stillbirth rates within countries related to socio-economic status. In both low- and high-income settings, stillbirth rates are higher in rural areas than in urban areas. African American women in the U.S. have nearly twice the risk of stillbirth compared to white women. Source: report by UNICEF, WHO, World Bank Group and the UN, A Neglected Tragedy: The global burden of stillbirths, containing first-ever global stillbirth estimates by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME)

Home births increase the risk. Over 40 percent of global stillbirths occur during labor, a loss that could be prevented with improved monitoring and the presence of a doctor, midwife or other skilled birth attendant (SBA) trained to recognize and manage obstetric emergencies. Home births have become more appealing to some during the pandemic, as a way to limit their exposure to coronavirus. Some women are skipping their antenatal (ANC) appointments for the same reason — not always by choice.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic caused critical disruptions in health services, many women in low- and middle-income countries lacked the timely and high-quality care needed to prevent stillbirths. Half of the 117 countries analyzed in the UN report have coverage that ranges from a low of less than 2 percent to a high of only 50 percent for key maternal health interventions, including C-sections, malaria prevention, management of hypertension in pregnancy and syphilis detection and treatment. Coverage for assisted vaginal delivery — a critical intervention for preventing stillbirths during labor – is estimated to reach less than half of pregnant women who need it, the report's data show.

Soha Mosleh recovers in the maternity ward of Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza, Palestine. In her ninth month of pregnancy, after leaving her home in the Zeitoun district to find a safe haven from escalating violence, she began experiencing vaginal pain. "It felt like a stone," she told UNICEF. She gave birth at the hospital to a stillborn baby girl. Her doctors attributed the loss to conflict-related stress. © UNICEF/UNI166910/d’Aki

During the virtual conference, health ministers, UN agency representatives, health data experts, midwives and others discussed the need to overcome these and other challenges. For its part, UNICEF has acclerated efforts to deliver critical health care services — including ANC, safe delivery and postnatal care, newborn care and immunizations — to vulnerable women and children as part of its global pandemic response.

"UNICEF proudly joins the call for a renewed commitment to prevent stillbirths," UNICEF Executive Director Henrietta Fore said. "It can be done."

Other priorities going forward include strengthening data collection and data quality to enhance evidence and knowledge, helping countries set targets and focus their investments accordingly, and eliminating the social stigma that is often associated with having a stillborn baby in some countries and cultures.

"Telling people that I lost the baby was so shameful," Akindoyin Oyelere shared in the event chatbox. "I felt so bad and I did not even want to talk about it then. But now I can talk about it. I don’t feel the shame anymore. I can now tell people that I lost a baby to pregnancy-induced hypertension that was undetected. Looking back to my experience, I wish the hypertension was detected, I wish I had seen my baby, I wish I had gone on maternity leave to deal with my loss, I wish I was not blamed, I wish I had had access to psychological support from a therapist. All these would have made a difference to my experience."

Awa Sonta sits on a bed at the regional hospital in Mali's Mopti region, Djenne district. She is recovering from delivery complications that resulted in the stillbirth of her baby. She had experienced three days of painful labor before being taken to a rural health center in the village of Mougna about nine miles from her home, on a cart pulled by two bulls, the only transportation available. An ambulance then transported her from the health center to the regional hospital. By the time she arrived, her uterus had ruptured, and the baby had died. The stillborn baby was delivered by emergency C-section. UNICEF supports the improvement of emergency transportation to hospitals and health centers. © UNICEF/UNI81224/Pirozzi

Top photo: Salima Bibi, 19, waits in the maternity ward of a hospital in Kolkata, West Bengal, India after arriving at the hospital two weeks before her due date, complaining of labor pains. Her pulse and blood pressure and her baby's fetal heart rate are stable, so now she is waiting for the doctor to come tell her if she will be delivering her baby today. Improved monitoring and better quality care during pregnancy and at time of delivery are critical to reducing preventable stillbirths. © UNICEF/UNI194346/Kaur