Inside Look: What's Really At Stake for Migrant Children and Families

In this Q&A, Rhonda Fleischer, UNICEF Migration Program Specialist, explains the intricacies of UNICEF’s work supporting and protecting migrant children and families in the United States — and how what happens at the U.S. border is but a brief part of a much longer, more complicated journey.

What's the situation for migrants today and how is UNICEF responding?

RHONDA FLEISCHER: Children and families continue to migrate to Mexico and the U.S. southwest border in relatively high numbers. Many are still unable to actually enter the country. Tens of thousands of families continue to be expelled to Mexico, Central America, Haiti or other countries in the region under a public health order (Title 42) that was put in place at the start of the pandemic last year.

Migrant children and women walk along a road in Guatemala, en route to Mexico from Honduras. © UNICEF/UN0401897/Volpe

UNICEF is concerned about the safety and well-being of children and families returned without adequate screenings and access to asylum processes. Our position is that it’s possible to protect the safety and well-being of children and families and also protect public health.

Earlier in the year, UNICEF worked alongside UNHCR and IOM to help the U.S. government wind down a policy that returned families to Mexico to wait out their asylum proceedings. And we have been helping with complex child protection cases for that initiative, while also building up reception capacity in northern Mexico. However, a court order has now required the U.S. government to reinstate that policy — commonly referred to as MPP, or Migrant Protection Protocols – at least temporarily.

All in all, this essentially “closed border” has meant large numbers of children continue to be returned to the dangerous conditions they fled – or are waiting in overstretched, dangerous places in northern Mexico.

All in all, this essentially “closed border” has meant large numbers of children continue to be returned to the dangerous conditions they fled – or are waiting in overstretched, dangerous places in northern Mexico.

One notable exception has been unaccompanied children.

How so?

RHONDA FLEISCHER: Beginning in February this year, the U.S. government exempted unaccompanied children from Title 42, and the number of unaccompanied children in government care hit a historic high during fiscal year 2021 (October 1, 2020 to September 30, 2021), significantly straining the reception infrastructure.

Jeison, 16, photographed in his home in Brentwood, New York, came to the U.S. at age 10 as an unaccompanied minor, traveling from his home country of Honduras. He walked for much of the journey and recalls seeing people hungry, and dying — "nothing I hadn't seen before," he says. © UNICEF

After a year of record low capacity in 2020 due to their expulsions under Title 42, there were less beds for unaccompanied kids in the shelter system and less trained staff to respond.

What was UNICEF doing during this time?

RHONDA FLEISCHER: UNICEF began providing technical support and training in one of several government-run emergency intake sites that were set up to care for unaccompanied children on military bases. We also began some work with Border Patrol on integrating more child-sensitive approaches into their training of agents. Our focus has been providing recommendations, training and technical support on approaches that would better support the mental health and psychosocial well-being of children in care.

This has all been a natural progression for UNICEF. We’ve been working for several years now with many of the community-based border shelters and other organizations on the front lines that serve families, developing resources on mental health and psychosocial support and providing training on interventions, such as psychological first aid for migrant children and families in distress. We also coordinate a community of practice to support the mental health organizations who provide specialized services for asylum-seeking families.

These teens made the dangerous journey from Latin America to the U.S. to be reunited with their families.

— UNICEF (@UNICEF) February 26, 2021

Every child needs family, community and belonging. pic.twitter.com/DKFbfMrrlQ

What does this work look like on the ground? Can you give us an example?

RHONDA FLEISCHER: Let me tell you a story. Lourdes (not her real name) was an 11-year-old girl who arrived with her mother in one of the shelters after fleeing Honduras. They came from the northern coast where there was really nothing for them after the hurricanes, and gangs were controlling whole communities.

When they arrived, Lourdes was in extreme distress. She’d been raped along the journey, and her mother was beside herself, trying to navigate their onward travel to their family in New Jersey, while also taking care of her daughter. We had been working with the shelter staff and volunteers on appropriate ways of responding in these situations – not just to provide a meal, shelter and information, but also to use simple techniques to provide immediate psychosocial support.

María (name changed), 16, was migrating from Honduras to the U.S. when she was detained by immigration officials near the border of Guatemala and Mexico and transferred to a temporary shelter for unaccompanied migrant girls and adolescents in Tapachula. She decided to migrate after Hurricane Eta ripped through her family's home, killing both of her parents in November 2020. UNICEF is supporting the shelter to strengthen child-centered care, which includes life skills development and psychosocial support activities through recreation and sports. “Their rights, resilience, self-esteem, and the power to lead their lives travel with them” said Ana Cecilia Carvajal, who monitors psychosocial support carried out by UNICEF partners in the field. “We want to provide them with support and to remind them of their worth and to help them think positively.” © UNICEF/UN0436838/Guerrero VII Photo

Through our partnerships, we have also been strengthening referral networks so that the shelter volunteer was able to link the mother with an organization in New Jersey who could help with their immediate needs and also connect them with health and mental health support. There is tremendous compassion amongst the staff and volunteers on the front lines. But there hasn’t been a formal system to build capacity and support their work, especially when there are these more complex cases. This is one of the gaps we’re working to fill.

At the same time, we are advocating for an overall system that would be more in line with the best interests of children. In Building Bridges for Every Child, a major report we released earlier this year, we’ve made specific recommendations for improving the overall system — such as having child welfare professionals lead on interviews with children at initial reception, scaling up family and community-based care rather than immigration detention, and increasing support to children and families once they’re released to local communities.

The recommendations were drawn from a series of convenings we hosted with different stakeholders – people in government, people who work for NGOs, policy makers, researchers. They also draw from global principles UNICEF applies in contexts across the globe. The purpose was to foster greater coordination and continuity of care across what is a large, diverse and uncoordinated system, especially after children are released to local communities.

What important points seem to keep getting lost in the larger conversation?

RHONDA FLEISCHER: A lot of attention is on the border, but I think what gets lost is that the border is one snapshot in time, only part of a much broader life journey for children and families. We quickly forget what life has been like in Central and South America and in the Caribbean, countries like Haiti and Honduras and Guatemala over the past year — and that children and families are also spending time in local communities in the U.S.

The increase in arrivals was really no surprise when you consider how the risks to children and families have become even more acute in the region. Violence, extreme poverty and other compounding factors have all worsened, aggravated by the pandemic, two major hurricanes, political instability and increased stigma and discrimination against migrants. Many Haitians who have been living in South America for years, having migrated long ago, are finding their situations no longer tenable.

UNICEF has been working to address the root causes of migration in all of these countries, while working to address immediate humanitarian needs and also supporting people’s reintegration after they are returned.

A child's drawing hanging up outside a Child Friendly Space that UNICEF supports at the migration reception center in Lajas Blancas, Darién, Panama. Most children crossing into Darién via the Darién Gap, a treacherous stretch of jungle, are the children of Haitian migrants, some of whom moved to Chile and Brazil after a devastating earthquake in 2010 and others who left more recently, after the August 2021 earthquake. With the COVID-19 pandemic, facing a lack of sustainable opportunities, racism and discrimination, many of these families with Chilean and Brazilian-born children are finding themselves on the move again. © UNICEF/UN0561643/Urdaneta

The other piece that gets lost is the fact that part of the reason children migrate to the U.S. is to reunify with family who are already here. Over 90 percent of unaccompanied children are released from government custody to biological parents or close relatives. And those newly arriving have become our neighbors, our friends, our children’s classmates. Not only do these children need support, but they contribute to our communities.

The other piece that gets lost is the fact that part of the reason children migrate to the U.S. is to reunify with family who are already there. Over 90 percent of unaccompanied children are released from government custody to biological parents or close relatives… [They] have become our neighbors, our friends, our children’s classmates. Not only do these children need support, but they contribute to our communities.

What's your role at UNICEF? What's been most frustrating for you working on these issues?

RHONDA FLEISCHER: I lead UNICEF’s programmatic response in the United States, while working to support UNICEF’s work in the region – as a part of a migratory-route based approach. We seek to leverage our unique role as a UN agency – focusing on advocacy and systems change, while also building capacity and preparedness based on our experience from humanitarian contexts around the world.

What’s been most frustrating for me is that we live and work in a country with tremendous financial resources and technical expertise in child welfare and related areas, yet there continues to be major gaps in applying those resources and expertise equitably, to all children, regardless of immigration status. We have the knowledge and capability to do this in a way that protects the well-being and dignity of children and their families. Yet we lack political will.

What's been most rewarding or gratifying? In what areas is UNICEF making the most progress or getting the most traction?

RHONDA FLEISCHER: I do think our direct support to staff and volunteers in community-based organizations, helping them provide basic and appropriate psychosocial support, has been particularly rewarding. There are so many people who carry out very difficult work on the front lines with unyielding compassion. Their capacity for human kindness is incredibly inspiring.

As for progress, we have seen a real eagerness for support navigating the complex mental health and psychosocial impacts of the adversity people have had to overcome. The unspeakable violence and exploitation families have endured.

Increasingly, we have been supporting organizations that serve migrant and asylum-seeking families in local communities as well — helping some of the most impacted communities develop coordination mechanisms and plans to better support newly arriving children and families, in schools, through integrated service hubs, etc. And we have been making progress in helping to strengthen good referral pathways across organizations – from the border to local communities — so that children will be supported at every step of their journey.

We have been making progress in helping to strengthen good referral pathways across organizations – from the border to local communities — so that children will be supported at every step of their journey.

In which areas has UNICEF had to pivot and why?

RHONDA FLEISCHER: We initially started our work with much more field presence. Like so many other organizations, with the COVID pandemic, we have pivoted to doing much of our work online and remotely. Like others, we’ve found that while there are some limitations, remote trainings and convenings have allowed us to engage with a much wider and more diverse groups of local governments, NGOs and community-based organizations.

Leveraging this, we are slowly and steadily building a growing network and are beginning to focus more on strengthening continuity of care from the border and in local communities throughout the U.S.

What gives you hope? What are some signs that the situation for migrating children and families might improve in the coming months?

RHONDA FLEISCHER: We have welcomed the recent indication that the U.S. government is committed to investing in measures that will help address the root causes of migration and to establishing legal pathways for migration – things like bringing back the Central American Minors program or establishing a Migrant Processing Center in Guatemala. These solutions take time to develop, but will ultimately be the most impactful and sustainable.

Jennifer, 16, above, and her two sisters Ana, 14, and Mariana, 20, made the long difficult journey north from Guatemala, eventually reuniting with their mother in New York after having been separated from her for five years. © UNICEF/UN0373319/Murphy/Principle Pictures

Also, the evacuation of Afghan families has required an unprecedented whole-of-government response. UNICEF’s role has largely been overseas in interagency coordination, identification and registration, child protection, family tracing and reunification efforts for unaccompanied and separated children.

I was honored to support this effort during the early weeks in Qatar. The rapid nature and scale of the reunification and resettlement efforts has not been easy, but it has enabled some innovative approaches that I think could be applied for all children in need of reunification and protection — regardless of where or how they arrive to the U.S.

How is UNICEF USA supporting or collaborating with UNICEF to support migrant children and families?

RHONDA FLEISCHER: Our work in the U.S. is very much a “One UNICEF” response – we work side by side on these issues to implement UNICEF’s global framework for action for uprooted children in the United States with an integrated strategy. While UNICEF leads on technical programmatic engagement, UNICEF USA leads on policy-related advocacy with Congress and at the grassroots level, as well as resource mobilization. We are very much one unified team, drawing from UNICEF’s global experience – as well as the power of UNICEF USA’s national and regional presence.

What can UNICEF and UNICEF USA supporters do to help?

RHONDA FLEISCHER: All voices are needed to call for policies that will expand legal pathways so children and families don’t need to take dangerous migration routes. And policies that will ensure migrant children are protected when they have no choice but to do so.

We also need help advocating to end policies like Title 42 and MPP that return families to danger and keep families separated across borders.

And we need funding. Our work in the U.S. is fully funded by private donations. Donations are what will allow us to strengthen the partnerships we’ve been building and to do much more for migrant children in 2022.

Alejandra, 10, is held by a UNICEF-supported volunteer at the St. Augustine hotel for refugees in Mexico. © UNICEF/Bindra

The rights of children do not stop at borders. Learn more about how UNICEF works to protect the rights of children on the move.

Help UNICEF support vulnerable children to ensure they get the protection, care and support they need to reach their full potential. Please donate.

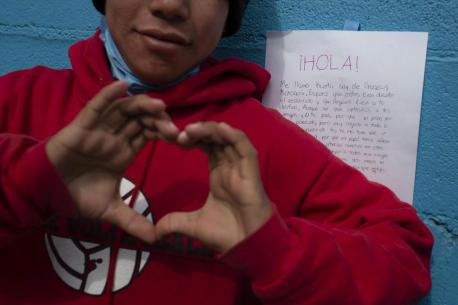

TOP PHOTO: A boy reacts to a letter of support he received from another Mexican teenager at a shelter for unaccompanied migrant adolescents in Tijuana, Mexico. © UNICEF/Bindra