Back to the Books: Literacy Empowers Girls Around the World

A quality education can open doors for girls and break the cycle of poverty. UNICEF is working to make sure students keep learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As schools reopen around the world, millions of children are entering physical classrooms for the first time since schools closed to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Experts are examining the risks and benefits of the in-person learning experience, looking at reopening from both a public health and quality of education perspective.

Evidence on the negative impacts of school closures is overwhelming, with long-term implications for children’s learning, safety, health and well-being. Long breaks from in-person education have been shown to be harmful to academic progress, with students losing an average of one month of their school-year gains in reading and math over summer vacation.

Global youth literacy rates have been rising steadily for decades; we can't let COVID-19 reverse that progress

It is imperative that schools open as soon as they can do so safely, in line with global health guidelines. Prior to the pandemic, UNESCO and the World Bank released data showing that 53 percent of children in low- and middle-income countries cannot read and understand a simple story by the end of primary school. High-quality education is a human right: the ability to read and write opens the door to a multitude of opportunities, empowering individuals to absorb information, think critically and be active participants in society.

Universal literacy among youth is a key target within Goal 4 of the Sustainable Development Goals, along with eliminating gender disparities that exist in access to learning. While the global youth literacy rate increased from 86 percent to 91 percent over the past two decades, regional and gender gaps are prevalent — literacy rates are lower in lower-income countries and higher among males than females by 7 percentage points.

A student looks up from her book at Ranitaria School in Rainandgaon, Chattisgarh, India. Surveys show that states like Chattisgarh are consistently below the national average in early literacy development. UNICEF is working with partners to strengthen Early Grade Literacy in all 1,838 primary schools of Rainandgaon, one of the largest districts in Chattisgarh. © UNICEF/UNI223645/Misra

Girls’ learning is disproportionately affected when a crisis hits

If schools remain closed for an extended period of time, the gains made in girl’s education over the past 25 years are at risk of being undone, particularly enrollment rates and learning outcomes. The threat of gender-based violence, child marriage and early pregnancy also greatly increase during a crisis. For example, during the Ebola outbreak in 2014, the pregnancy rate among teenage girls in Sierra Leone doubled and many girls did not continue their education once schools reopened. When girls are at home, they are often called upon to care for sick relatives and do unpaid housework, detracting from the time they could spend learning and developing reading and writing skills for a brighter future.

Girls wear masks on their first day back to school at Aisha bent Al Mo’meneen School in Amman, Jordan. Going back to school is especially important for girls, children with disabilities, children living in poverty and refugee children – those who are hardest hit by school closures. © UNICEF/UNI364476

Increased literacy rates improve the future of girls and their communities

An investment in the education of girls is an investment in their future and in their communities. Women’s participation in society is key to development; literate women contribute to the economic prosperity and security of their countries.

Women with a secondary school-level education can expect to earn almost twice as much as their counterparts with no education at all, empowering them to support themselves and their families, breaking the cycle of intergenerational poverty. Without the ability to read and write, women may be limited to occupations focused on child care and housework, which are often unpaid or underpaid.

Each additional year of secondary education is associated with a significant reduction — five percentage points or more in some countries — in the likelihood of a girl marrying and having a child before the age of 18. Ending child marriage and delaying childbearing allows girls to be autonomous in the pursuit of their vocational goals, curbs population growth and enhances decision-making for their future children’s health care and nutrition.

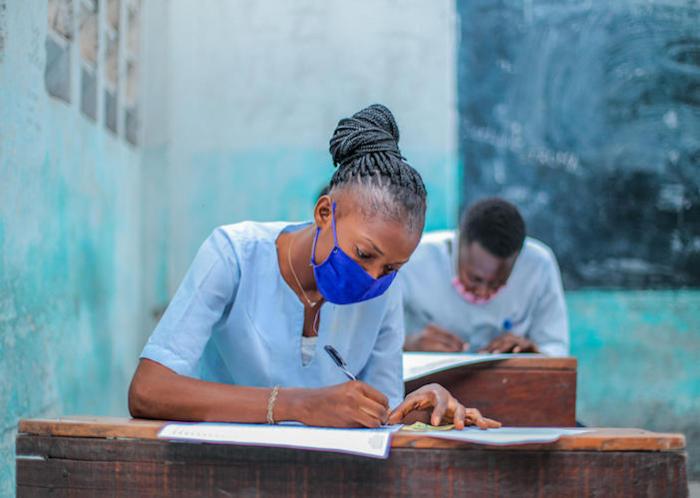

In her final year as a secondary school student in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo, Elodie sits for an exam while wearing a mask to prevent the spread of COVID-19. © UNICEF/UNI367487/Mulala

The Keeping Girls in School Act empowers girls around the world through education

UNICEF partners with governments in 157 countries to advocate for gender equality in primary and secondary schools, targeting the more than 130 million girls between the ages of 6 and 17 around the globe who remain cut off from education. The bipartisan Keeping Girls in School Act works to address barriers that stop girls from attending school by harnessing the power of the United States government through smart investments and coordination.

Top photo: Girls on the playground of their school in Toumodi-Sakassou, in central Côte d'Ivoire. Students are happy to see their friends again now that classes have resumed, after being closed to prevent the spread of COVID-19. © UNICEF/UNI333572/Dejongh