Why the Flores Settlement Matters

Both family separation and detention are bad for children. Please join UNICEF in speaking out to protect refugee and migrant children.

For over 20 years, the Flores Settlement has required the U.S. Government to release children in detention as soon as possible to their parents, guardians or relatives.

In early September, the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Health and Human Services proposed regulations that would allow children to be detained indefinitely. Both family separation and detention are bad for children. Please join our UNICEF UNITE grassroots advocates in speaking out to protect refugee and migrant children.

What is the Flores Settlement and why does it matter?

In September 2018, there were 12,800 child migrants held in government facilities in the United States – the highest ever recorded. And this figure does not include the children held in detention centers with their families. That same month, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) proposed a regulation that would override child protections established by the Flores Settlement. The proposed regulation would, among other things, allow the indefinite detention of migrant children.

The Flores Settlement

In 1985, 15-year-old Jenny Flores fled the civil war in El Salvador and sought refuge in the U.S. More than 75,000 people (30,000 civilians) died during the war, including her father. Flores was arrested upon arrival in the U.S. and then spent two months in a detention facility in Pasadena, CA. There, Flores was incarcerated with adult strangers and provided with “no educational or other reading materials; no adequate recreational activity; and no medical examination.” She was also “denied any visitation with family or friends.”

Upon learning that Jenny’s experience was not unique, but rather part of a larger, systemic disregard for the well-being of children in the detention centers, the National Center for Immigrants Rights, National Center for Youth Law and the ACLU filed a class action lawsuit. More than a decade later, the case was settled with the stipulation that the U.S. government implement several child protection protocols. These protocols, which came to be known as the Flores Settlement, include placing children in state-licensed and child-appropriate facilities, offering educational services and providing routine medical care.

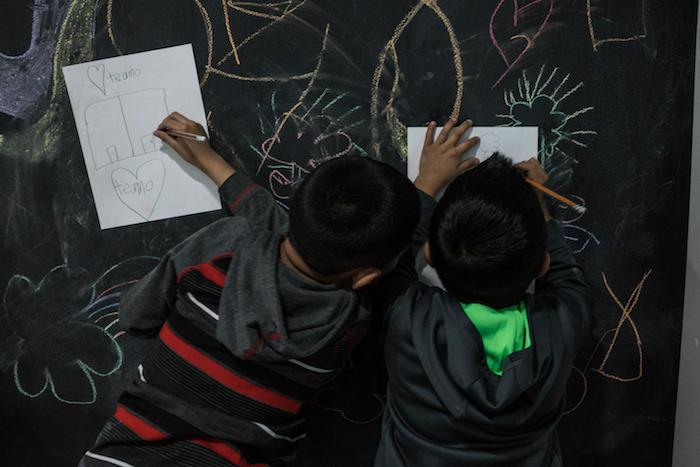

A child's drawing in a detention center is titled "Sad. Disappointed." © UNICEF/UN030701/Zehbrauskas

The current proposal

Both the Obama and Trump administrations issued challenges to the Flores Settlement, arguing that long-term incarceration was the only way to avoid separating families when parents were detained. The presiding judge, Dolly M. Gee, rejected both challenges on the grounds that the logic presented in favor of indefinite detention was “dubious and unconvincing.” Now, DHS and HHS are using that same logic in a proposal to eliminate two of the Flores Settlement’s crucial child protections:

- Requiring the release of minors “without unnecessary delay,” which has been interpreted to mean 20 days, and

- Treating minors with “dignity, respect and special concern for their particular vulnerability…[by placing] each detained minor in the least restrictive setting appropriate.”

If implemented, the proposed changes to the Flores Settlement would be unreasonably expensive and trauma-inducing.

Detention is no place for a child. © UNICEF/UN0217823/Bindra

The cost of detention

The daily cost, known as the average daily “bed rate,” of migrant detention lies somewhere between $127 and $319, depending on the information source. Whichever figure is used, the cost is remarkably high. Alternatives to detention (ATD), on the other hand, are far less expensive and incredibly effective. ATDs cost roughly $6 per day and utilize GPS monitoring devices, check-ins and other case management programs. ATDs have been found to be 95% effective. One U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) ATD program, in particular, had a 99% compliance rate.

Detention is also incredibly harmful to the short- and long-term well-being of children. Studies by organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) about detained, unaccompanied immigrant children in the U.S. found high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation, among other traumas. The solution, however, is not to detain entire families because it, too, is harmful and traumatic for children. Even the ICE Advisory Committee on Family Residential Centers concluded that “DHS should discontinue the general use of family detention.”

Ultimately, detaining children for immigration purposes is a violation of their basic rights. Doing so indefinitely is harmful and unnecessary, particularly when there are effective community-based alternatives to detention. If the crucial child protection tenets from the Flores Settlement are undone, as the proposed regulation seeks to do, then the U.S. will likely proceed to detain thousands of children indefinitely, without due process.

To advocate on behalf of the world's children and connect with other UNICEF supporters in your community, we encourage you to join UNICEF UNITE. Visit unicefunite.org for more information.

Top photo: A view from the McAllen-Hidalgo-Reynosa International Bridge in McAllen, Texas in June 2018. © UNICEF/UN0220987/Bindra