The Long and Winding Road: In the world’s far corners getting vaccines

The itinerary is ambitious: It begins with a flight from POLIO MANUFACTURER LOCATIONTK to Islamabad, followed by a road trip by jeep for hundreds more miles. Then when the road runs out, it’s on foot from there. A donkey carries the cargo over the rocky hills, with packs securely fastened to keep them from slipping off. The trail continues for mile upon desolate mile, until a small village appears on the horizon, the tiniest of dots on the map.

This is not the travel plan of an overly adventurous trekker. It is the path a UNICEF polio vaccine must take to reach children in just one remote community in Pakistan, one of the last countries on earth where the crippling childhood disease remains endemic.

Getting any vaccine to the world’s most vulnerable children takes both technical and logistical ingenuity. To stay effective, vaccines for polio, measles, rubella and tetanus must be kept consistently cold — at or close to freezing — from the point of manufacture right until they are administered. This can be especially difficult when a vaccine is crossing time zones, moving over rugged land or traversing areas embroiled in conflict. The longer it travels the greater the risk; all it takes is one crack in an insulated storage container to render a vaccine useless.

Keeping a vaccine’s temperature constant — or maintaining the “cold chain,” as it’s called — is but one challenge of global immunization efforts. In Nigeria, for example, where UNICEF and Rotary International have been partnering since 1988 to end polio, violence has both interfered with the delivery of vaccines and endangered the lives of those who administer them. Misinformation and rumors about vaccine safety can also get in the way. Reaching nomadic populations, educating parents and galvanizing community support are other hurdles. All of which makes the recent good news out of Nigeria — one full year with no new cases of wild poliovirus — all the more impressive.

But it starts to make sense when you consider the dedication and resourcefulness of the individuals working at every twist and turn of a vaccine’s journey: The Nigerian government, thousands of health workers, countless community and religious leaders and international coalitions like the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, which UNICEF and Rotary International helped spearhead in 1988 all played vital roles to make a polio-free Nigeria even possible.

Vast public health initiatives can make a lifesaving difference — and build a global network of people united to give every child, everywhere, a chance at a better life. Here, a look at who they are and how they operate.

By air, by sea, by reindeer

Getting vaccines to the children who need them can be logistically challenging, even physically grueling. On its path from manufacture to child, vaccines travel by airplane, boat, truck, motorbike, even reindeer. To retain its life-saving benefits, the precious cargo must be kept cold every step of the way.

© UNICEF/NYHQ2014-1524/Makundi Somalia

© UNICEF/NYHQ2014-1524/Makundi Somalia

Workers load polio and measles vaccines along with medicine and therapeutic food onto a plane in Mogadishu, Somalia, for transport to those previously cut off from humanitarian aid. After a May 2014 measles outbreak, UNICEF piggybacked an emergency vaccination campaign onto its anti-polio efforts to prevent further spread of the disease.

© UNICEF/NYHQ2011-2453/Sokol

© UNICEF/NYHQ2011-2453/Sokol

Polio vaccines from a storage facility in Juba, South Sudan, arrive at Aweil Airport. The vaccines travel in insulated shipping containers that keep them at or close to freezing to preserve their potency.

© UNICEF/NYHQ2011-2579/Zaidi

© UNICEF/NYHQ2011-2579/Zaidi

In Pakistan, one of the last three countries where the wild polio virus is endemic, Rotary health workers (in green caps) travel by boat to immunize the children of Karachi’s Bath Island. Since Rotary, UNICEF’s partner in the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, launched its polio immunization program in 1985, it has spent more than $107 million to end polio in Pakistan with the help of volunteers from Pakistan’s 173 Rotary clubs.

© UNICEF/NYHQ2011-2459/Sokol

© UNICEF/NYHQ2011-2459/Sokol

A Social mobilizer and vaccinator from a UNICEF-supported health center speak with a mother outside her home in South Sudan’s Unity State about vaccinating her 2-year-old son against polio.

© UNICEF/NYHQ2015-1133/Bindra

© UNICEF/NYHQ2015-1133/Bindra

In Sierra Leone in April, health workers financed by UNICEF and partners went door-to-door to administer vitamin A, deworming tablets, vaccinations and nutrition screenings to young children in a village devastated by the worst Ebola outbreak in history. They are part of a national campaign to reach the 1.5 million children under the age of 5 in Sierra Leone, which is still struggling to mend its Ebola-ravaged health care system.

© UNICEF/UNI162702/Yurtsever

© UNICEF/UNI162702/Yurtsever

Turkish Ministry of Health workers make house calls to invite parents, like this father of seven who fled violence in Aleppo, Syria, to the local health center, where children can be inoculated against polio. In nearby Syria, where polio outbreaks have occurred, some children have yet to be vaccinated, increasing chances that the disease could spread across borders.

When disaster strikes

In times of crisis, UNICEF routinely administers vaccines as part of emergency relief efforts at refugee camps and in communities that need humanitarian support after cyclones, earthquakes or floods. Though tragic, a humanitarian emergency can sometimes present an opportunity to immunize children who might not otherwise have been reached.

When violence forces families in places like Syria and South Sudan to flee, UNICEF and its partners must work even harder to prevent lapses and immunization gaps that can increase risks for an entire region. A recent study in The Lancet found that gaining parent and caretaker support for vaccination programs, particularly in regions beset by conflict, poses other obstacles. Polio’s recent resurgence in Syria — where four years of crisis is being blamed for 2014’s first polio outbreak there since 1999 — shows how such chaos threatens children’s lives and why swift and thoughtful action is so important.

© UNICEF/UNI181195/Sevenier

© UNICEF/UNI181195/Sevenier

Born just a week before Cyclone Pam hit Vanuatu, on March 13, this little girl got her first polio vaccination by a UNICEF team in Etas, while her family struggled to recover from the loss of their home and village.

© UNICEF/NYHQ2015-1532/Bannon

© UNICEF/NYHQ2015-1532/Bannon

Burundian families who’ve fled political instability at home line up at Rwanda’s Mahama refugee camp to get their children polio and dual measles and rubella vaccinations as well as vitamin A supplements and deworming tablets during a UNICEF supported campaign. Most of the more than 27,000 refugees — including close to 10,500 children — from Burundi live in the camp, where UNICEF is seeking to prevent diseases from spreading to host and neighboring communities.

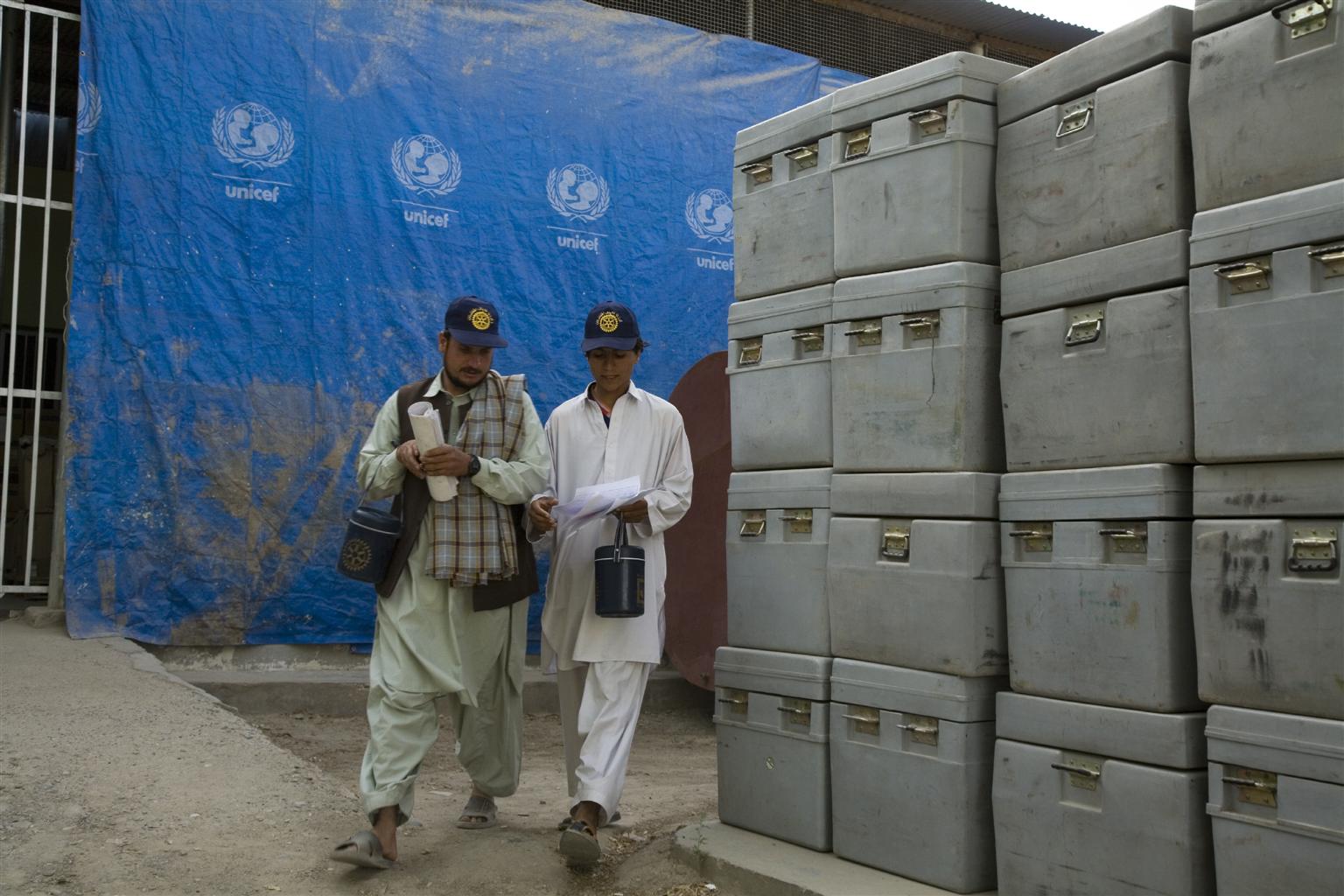

© UNICEF/NYHQ2007-1077/Noorani

© UNICEF/NYHQ2007-1077/Noorani

For vaccinators, like these Rotary International workers in Afghanistan, skirting conflict is a serious challenge but doable when all sides agree to put children first. Warring factions in Afghanistan called a ceasefire during a 2007 polio immunization drive so children could be immunized. The bravery of Rotary vaccinators who work in polio-endemic Afghanistan and Pakistan protects children within those borders and in the Middle East, where the disease spread last year to Syria and Iraq.

The Finish Line

Once child and vaccine finally meet, inoculation can be as easy as squeezing the end of a dropper. But the work doesn’t stop there. Keeping track of who is reached and educating parents and caregivers about what’s next is crucial. Some immunization campaigns chart their progress by providing vaccinated children with certificates or marking their fingers with ink to show that they are now protected. Fostering awareness of how immunizations work — how many doses it takes to immunize depends on the child’s health and nutritional status — is key to protecting the lives of all children.

© UNICEF/NYHQ2013-1317/Ohanesian

© UNICEF/NYHQ2013-1317/Ohanesian

A little girl from Somalia receives a dose of oral polio vaccine during an emergency immunization campaign UNICEF and partners waged in 2013 after Somalia experienced its first rash of cases since 2007.

© UNICEF/NYHQ2001-0008/Pirozzi

© UNICEF/NYHQ2001-0008/Pirozzi

For 30 years, Rotary members have assisted in the fight against polio in every way: through fundraising and advocacy at home and by administering vaccines to children out in the field. Here UNICEF Special Representative Mia Farrow, who contracted polio as a child but recovered, gives an infant a polio vaccine during January 2001’s National Immunization Days in Nigeria, part of a global effort led UNICEF, Rotary International, the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

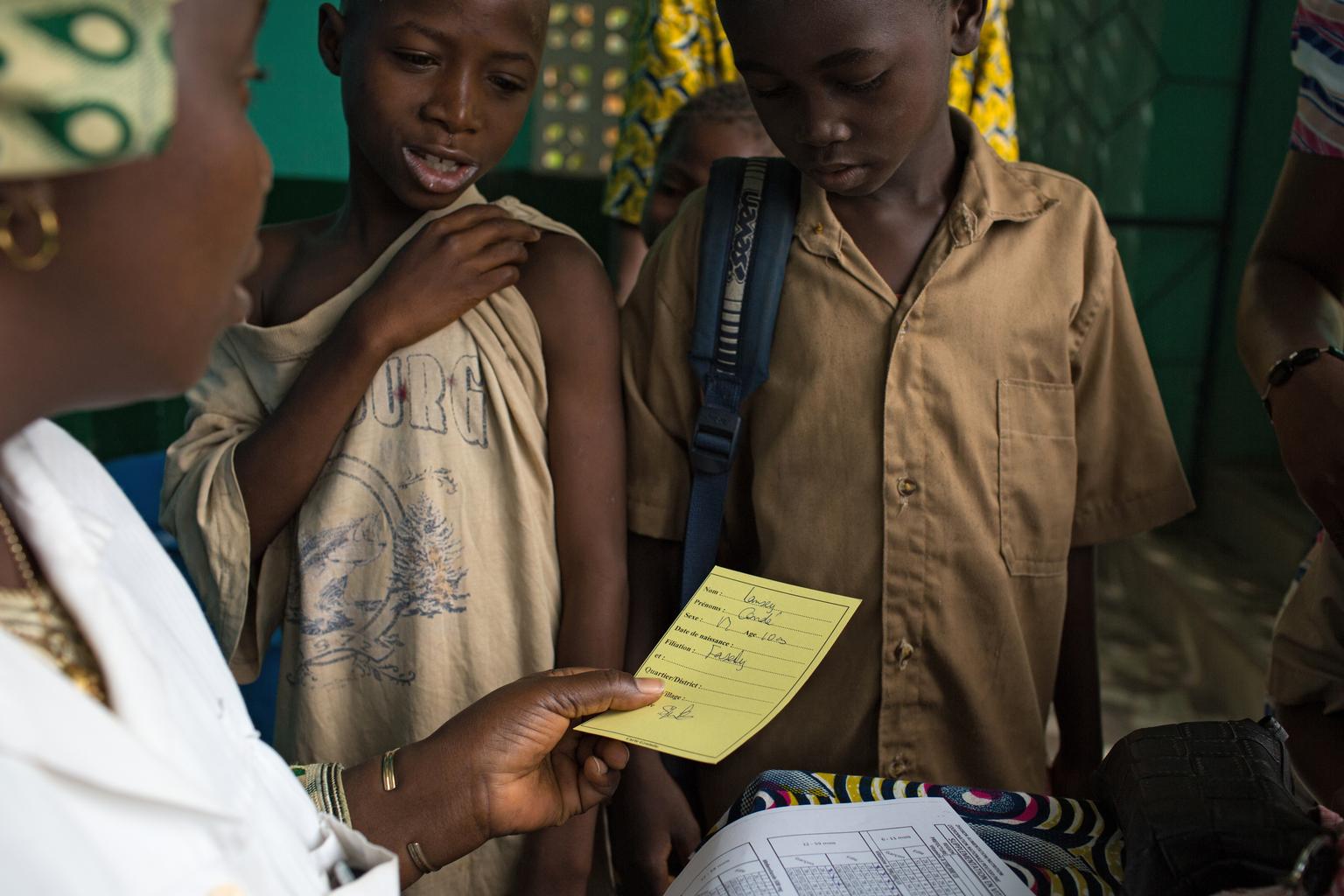

© UNICEF/UNI183271/Bindra

© UNICEF/UNI183271/Bindra

A nurse gives children their vaccination cards to show they received measles and polio vaccinations, as well as deworming pills and Vitamin A supplements at the Madina Health Centre in Guinea. In April, for the first time since the Ebola outbreak, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, resumed with UNICEF’s help, nationwide immunization campaigns to protect more than 3 million children from deadly preventable diseases.

© UNICEF/NYHQ2011-2595/Zaidi

© UNICEF/NYHQ2011-2595/Zaidi

A red pinky is proof this little girl from Pakistan is one-step closer to immunity against polio.