Inside Look: Centering the Best Interests of Immigrant Children

A Q&A with Olivia Peña from the Texas office of the Young Center for Immigrant Children's Rights about the group's legal and advocacy work on behalf of unaccompanied migrant children in U.S. custody.

Eitan Peled, who until recently managed UNICEF USA's Child Migration & Protection Program, connected with Olivia Peña from the Young Center for Immigrant Children's Rights, to discuss the group's work, the critical role of their volunteers and how the organization is filling an urgent need for legal and advocacy services as the number of children in U.S. custody steadily increases. The Young Center is a UNICEF USA grantee.

Please tell us a little bit about yourself, your organization and your role there.

OLIVIA PEÑA: I’m a DPD — Deputy Program Director — for the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights based in our Harlingen, Texas office. I oversee our staff and work in San Antonio and Houston as well. Primarily my job is to guide and support our staff who are appointed as independent child advocates for unaccompanied and separated immigrant children in federal custody.

Once taken into U.S. custody [by the Department of Homeland Security] these children have a legal right to certain protections pursuant to the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act. I also support our national child advocate program, helping to develop different policies in collaboration with our policy team and with local community activists who are in the Rio Grande Valley working with us to further the best interests of children.

How did you end up working in this field?

OLIVIA PEÑA: I was a child immigrant from Mexico myself. I immigrated to the United States when I was six years old. I grew up in Brownsville near the border with Matamoros, minutes away from the Brownsville International Gateway Bridge. I lived the immigration journey, and I experienced the struggles that come with it. That is partly why I went to law school. I wanted to learn the law and then come back and serve the community where I grew up, to provide affordable services to those who are experiencing the same struggle.

I was drawn to the Young Center because of their holistic approach toward children and advocacy. There’s the legal side of course, involving immigrant visas, applications for asylum, green cards. But these children need other kinds of support too. They are in an unfamiliar country where people are speaking a language they don't understand, surrounded by adults they don't necessarily trust. Being able to help them from that angle — looking out for their best interests and goals, thinking about their safety and their other needs and wants, making them feel welcome — it was this approach what drew me to the Young Center and it is what has kept me here for the past six-plus years.

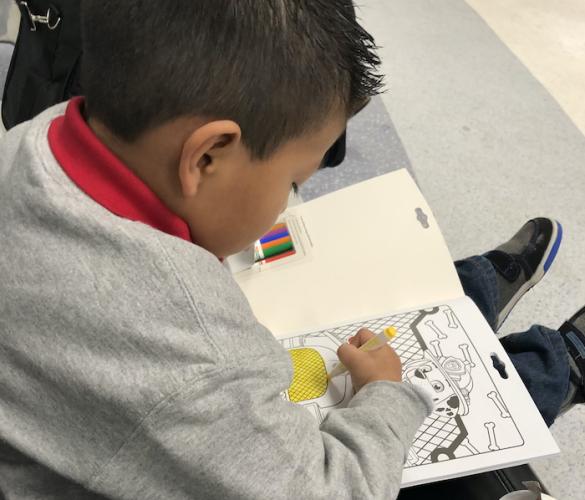

A 5-year-old boy who had been separated from his parent after the two arrived at the U.S. border, and spent a year away from family while in U.S. custody, waits to board a plane. After making a best interest determination and advocating for the child in court, the Young Center for Immigrant Children's Rights advocated for the child's safe return, where he reunited with his loved ones. © Photo provided by the Young Center

So, these kids — they come from different parts of the world, fleeing all sorts of situations...

OLIVIA PEÑA: Definitely. Some might wonder, why would these children risk the journey to go through such a difficult process? But a lot of the children and families we work with are running from violence. Death threats. Extortion. For these parents, the choice is to make the journey or stay in a home country where every day they are thinking, “Someone is going to kill one of my children or they are going to kill all of us.”

We also encounter a lot of cases of domestic violence. In many countries, there is little to no protection for women and children from their abusers. Some of the children we work with are survivors of sex trafficking or forced labor. For these children and families, they are leaving an unsafe situation. They have tried to get help, but no one has been able to help them. They have reached the point that “anywhere is better than where I am right now.”

Many countries don't necessarily have all the resources they need to help these individuals succeed and thrive. So, their only choice is to seek safety in another country, a country that has resources — or at least more resources — to help them upon arrival, to help them improve their situation.

What happens when they get to the U.S.? At what point does the Young Center step in?

OLIVIA PEÑA: Mostly we serve children who travel on their own, though we do also help the families of these children to help them achieve stability in the United States.

So, a child will travel to the United States — either unaccompanied or with a relative, and sometimes they're separated from that relative. When they reach the border, they are apprehended and processed by immigration officials. Their basic information gets recorded into a federal database. Within 72 hours, border patrol officers are supposed to transfer these children into protective custody overseen by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The idea is that children who are in ORR custody will then get the services they need — shelter, education, medical services — while they await release to sponsors. Their cases for legal protection will move forward and steps will be taken to reunify them with a relative who is already living in the United States.

But, as we all know, this may or may not happen, or it may take time to happen. This is where we come in. Usually, ORR or shelter staff will refer cases to us through our portal, which is also accessible through our website. But really, anyone can refer a case. We get referrals from ICE, from medical professionals, from other organizations, even from judges. That has been one of the nice things about being around for so long. We are a trusted organization. Our services are seen as essential. We are filling a gap.

Unfortunately, we don't have the capacity to take every case that gets referred. We have to prioritize and take the cases where we believe we can make the most difference. With the number of kids in custody steadily increasing, the need for our services is becoming more and more urgent, so we are constantly working to increase our capacity.

Each case is assigned to a volunteer who then works with a staff attorney or social worker to learn the child’s story and develop an advocacy plan for that child. All our volunteers undergo a two-day training, which covers a lot: who are the children we serve, what are the different forms of trauma, how to help a child process trauma and how to gain that child's trust. The volunteer's most important tasks are to accompany the child and learn the child's story. There are some horrific stories, so the training — along with ongoing support — helps volunteers manage that.

We serve children from Central America, but we also serve children from India, Romania and elsewhere. Some of our volunteers speak other languages or have professional backgrounds that might make them a good match for a child. Our team will meet with the child once a week, then work together to figure out which services the child will need — medical, educational, mental health support, legal relief support — and think through how to go about getting those services for them.

With the number of kids in custody steadily increasing, the need for our services is becoming more and more urgent, so we are constantly working to increase our capacity.

Any individual stories to share?

OLIVIA PEÑA: There was this one case, an adolescent boy who had come to the U.S. from Central America when he was 14. He had been in custody for about three months, and it had become clear that it would be unsafe for him to be returned to his country of origin. So, our goal was to help him achieve permanency in the U.S.

But then he was diagnosed with a terminal illness. And he decided that if he was doing to die, he wanted to die with his loved ones in his home country. To him, the most important thing was being with family for whatever length of time he had left.

His advocate met and supported him throughout this situation. The entire time she was meeting with him every week, visiting him at the hospital sometimes. And Young Center staff were helping her navigate that, making sure that she was keeping healthy boundaries while at the same time supporting the child since he was here alone without family. It was helpful to have the advocate next to him when doctors would come into his hospital room to tell him things, especially because Spanish was not his primary language.

Had we not had that advocate develop that relationship with him, I think it would have been easy for the government actors to say, this child needs to stay in the United States. This child needs to get access to all the medical attention that the U.S. can provide better than his home country. And while that may be true, our goal was to advocate for his best interests, to honor his wishes while also keeping him safe and with access to the necessary services.

This is where our network is super helpful. We were able to work with different partner agencies to create a safety plan for him, to make sure he could get medical services, lodging, transportation, and case management services so that when he did go back, he had access to all of that, and he could be with his family and still be safe.

It was a difficult situation to navigate. And unless you have support services, you won't really understand what it is to have a child returned to your care with an illness; when before you couldn't provide the basics, and now you have to provide heightened services.

Agustin, 17, from Guatemala (name changed) holds up the necklace his mother gave him for good luck before he joined a migrant caravan heading north. He had been staying at a shelter for unaccompanied adolescent migrants in Tijuana for nearly a month when the photograph was taken. “I want to go to Boston where I have an aunt," Agustin said. "I can study there and become an engineer and continue dancing and choreographing." © UNICEF/UN0284826/Bindra

It was crucial to have an advocate who could drive three hours every week, spend an hour with this now 15-year-old child, spend another hour drafting a summary of their visit; a volunteer who could accompany him during his hospital stays, and give her honest assessment, which then helped me submit a strong best interest recommendation, making sure all the agencies dealing with his case had all the facts.

This case is a great example of how intensive our work can be, and how collaborative we must be as well; how goals can shift midstream, and the critical role our advocates play in making sure children have a voice every step of the way and making sure that voice is heard. It's always a team effort.

Wow. And who defines what is the 'best interest' of a child? Who has to consider it, who doesn't?

OLIVIA PEÑA: The Convention on the Rights of the Child is what guides our work. Unfortunately, "best interests" are not codified in any of our immigration laws. And the U.S. hasn't ratified the CRC.

Immigration proceedings are designed for adults. Believe it or not, there's no requirement that immigration judges, border officials or DHS even consider what's best for the child. There is no best interest standard. Even though the court allows advocates to make recommendations, there's no mandate that the court must take those recommendations into account; they are not required to consider a child's safety, family unity, identity, freedom or development — all the important things. Every state law has a 'best interest' mandate incorporated into their family law and family court proceedings, but the United States as a federal entity does not. But this is where we come in, and through our advocacy work, we have been able to impress upon those deciding these cases the importance of best interest considerations.

So, it's a win just to get appointed, to have an opportunity to advocate for a child's best interests — nobody has to listen to you. I think this makes the Young Center's success with these cases that much more remarkable.

OLIVIA PEÑA: Thank you. I'm proud to say that about 80 percent of the time our best interest recommendations are granted. Our team in Harlingen— which has grown from two people to 10 in the last six years— works very hard. And we're seeing a bit of a ripple effect, where one judge will call for a child advocate, and then that influences another judge to do the same in a different case. A judge will see a 5-month-old child in front of them and say the child should have a child advocate or attorney before I move forward. Decision makers are seeing the value of what we do more and more, and this is very encouraging.

Good news for sure. Can you talk a bit about how our organizations work together?

OLIVIA PEÑA: The funding support from UNICEF USA has allowed us to expand our services and serve more children. But it's not just about funding. It's a collaborative relationship too. Say we need to locate a relative, or we need to access a birth certificate or a death certificate. Or we need to connect to one of the government agencies in a child's country of origin. In those instances, we have been able to reach out to you all for support. That's been extremely helpful, given UNICEF's vast global network, and connections to so many agencies on the ground. Just knowing that we can email one of you at UNICEF USA or someone at UNICEF and ask, "Can you please help with this case?," is huge.

Another thing is being able to refer UNICEF as a resource for other organizations and other legal service providers. We can say, "Hey, we're unable to help you at this time, but UNICEF may. Why don't you reach out to this person?" For us, it is important to be able to help other community organizations on the ground. And knowing that UNICEF is there helping to ensure that children who are sent back have what they need to make their way back safely is also super important to us.

How has COVID-19 impacted your work?

OLIVIA PEÑA: Everyone has had to pause and rethink how we are providing our services. We went from in-person visits and working in offices or community settings to doing everything virtually. The work we do is already difficult and going virtual has only made it more so. But thankfully we are still managing to provide comfort, build trust and convey our genuine desire to help. Keeping children engaged, getting them to open up and share their stories takes time, and we're still learning.

Two teenage girls from Central America connect at an open shelter for unaccompanied migrant adolescents in Tijuana, Mexico. UNICEF works with partners up and down the migration corridor to make sure the rights of migrant children and families are protected. © UNICEF/UN0284775/Bindra

Of course, going to court has also changed because of COVID. Some places within the nation still have court hearings going on. Some are doing them virtually, others don't have virtual courtrooms, so maybe they have conference calls. Some children are still being transported.

Our advocacy within this new setting is advocating for children to not have to go to court, to not have to wait in a parking lot, to not have to be exposed to other people. And so, our work is focused on avoiding exposure and making recommendations to see if they can get continuances.

The upside is we can "be there" virtually for a court hearing anywhere in the country. And we can recruit and train volunteers nationwide now too, because all the child visits are virtual. We are always looking for more volunteers.

What would you say are your most acute needs right now, to help you do your job?

OLIVIA PEÑA: We need a law that tells every single government actor that children's best interests must be considered in every single decision. That would certainly make our work easier. We wouldn't have to fight as hard or explain our thinking. We could just point to the law when making our recommendations.

Also: we need more people to realize that migrant and refugee children are children first and foremost, and that regardless of where they came from or why they came here, they need help and protection and it is our job, our duty to help them.

We need to change the narrative.

OLIVIA PEÑA: Yes. And donations always help.

Learn more about UNICEF's work to make sure every child is safe and protected.

Take action to help protect vulnerable asylum-seeking children and families.

Top photo: Olivia Peña sits with a 5-year-old boy who is about to board a return flight to his country of origin after being separated from family for over a year. In that time, he forgot his native tongue. The Young Center for Immigrant Children's Rights provides advocacy and legal services for unaccompanied migrant children coming into the U.S. © Photo provided by The Young Center