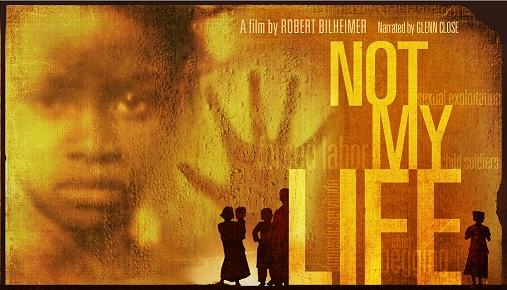

Dallas School Hosts A Not My Life Screening

Henry Goldberg, President of the St. Mark's UNICEF High School Club, reflects on how students reacted to the issue of human trafficking and watching the documentary, Not My Life. There were students from four different high schools in North Texas in attendance.

My name is Henry Goldberg, and I am a junior at St. Mark’s School of Texas, located in Dallas. After seeing Caryl Stern speak at our sister school, Hockaday, last year, I was inspired to start our own UNICEF Club at St. Mark’s. During the school year, I met with Hannah Wright, UNICEF’s North Texas Community Engagement Fellow. She suggested that we host a film screening of Not My Life for St. Mark’s, Hockaday, Greenhill, and any other local high school UNICEF clubs that wanted to participate.

During the weeks leading up to the screening, I feverishly advertised the event. People repeatedly asked me, “Will it be fun?” Having already seen the film, which is heartbreaking and extremely powerful, I responded “Fun? Not really. Moving and enlightening? Yes.”

The evening of the screening, I watched people slowly trickle in. From the way they were talking, I could tell they had come for the social aspect of the event. Most of the crowd seemed to have simply come to be with their friends, perhaps to escape the Thursday night homework load for an hour or two. Sure, human trafficking concerned them, but most of them didn’t know enough about it to truly understand the magnitude of the issue.

I was both surprised and delighted: we had a full house! Almost all of the one hundred or so seats were taken. Once the crowd settled down a bit, Rajya Atluri (Hockaday’s UNICEF High School Club president) and I walked up to the podium at the front of the room and addressed everyone by opening with some UNICEF and child trafficking true-false questions. I could feel the audience's shock when we said that 17,000 children die every day from preventable causes. At that point, I knew we had gotten the people’s full attention.

Although there was still a lot of socializing and chatter going on as people tried to guess the answers during the true-false questions, the atmosphere quickly shifted directly following the movie. You could have heard a pin drop. The film had ended, but every single eye in the room was glued to the screen. Nobody spoke a word. Before the showing, the people in the room might have expressed some concern about human trafficking. But by the time the display faded to black, each person cared deeply about the problem. Hannah Wright walked to the podium to start the discussion, but even after she asked her first question, “What struck you most about the movie?” the stupor continued. Not a soul moved. Finally, after twenty seconds of waiting, I raised my hand and answered: “How widespread the issue is.”

Even after I had broken the ice, only Rajya felt comfortable answering. I could tell from the expressions on everyone's faces that their silence was not simply teenagers being predictably reticent in an educational setting. Every person in the room had been moved by the screening. Gradually, students started opening up again, talking more and more freely about what they had just watched. I smiled and was satisfied: I knew we had reached our goal. We had created numerous new activists in the fight against human trafficking, and we were happy to stimulate change.